Next: FEW-NUCLEON SYSTEMS

Up: Dynamical (Chiral) Symmetry Breaking

Previous: Pion-Pion Lagrangian

Nucleon-Pion Lagrangian

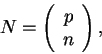

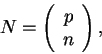

We are now ready to consider another set of composite particles,

the nucleons. We know that there are two nucleons in Nature, of almost

equal mass, the neutron and the proton, so they can be combined into the

iso-spinor

|

(40) |

where  and

and  are the Dirac four-spinors of spin 1/2 particles.

We have already attributed the isospin projections to quarks, Eq. (26), by placing within the quark iso-spinor the quark up

up and the quark down down (sounds logical?). Since the proton is

made of the

are the Dirac four-spinors of spin 1/2 particles.

We have already attributed the isospin projections to quarks, Eq. (26), by placing within the quark iso-spinor the quark up

up and the quark down down (sounds logical?). Since the proton is

made of the  quarks, and the neutron of the

quarks, and the neutron of the  quarks,

their isospin projections are therefore determined as in Eq. (40). In nuclear structure physics one usually uses the opposite

convention, attributing the isospin projection

quarks,

their isospin projections are therefore determined as in Eq. (40). In nuclear structure physics one usually uses the opposite

convention, attributing the isospin projection  =

=

to a

neutron, in order to make most nuclei to have positive total isospin

projections

to a

neutron, in order to make most nuclei to have positive total isospin

projections

0. All this is a matter of convention; one could

as well put the quark up down and the quark down up - the physics

does not depend on that.

0. All this is a matter of convention; one could

as well put the quark up down and the quark down up - the physics

does not depend on that.

Anyhow, the nucleons contain not only the three (valence) quarks, but

also plenty of gluons, and plenty of virtual quark pairs, and we are

unable to find what exactly this state is. Therefore, here we follow the

general strategy of attributing elementary fields to composite

particles. Before we arrive at sufficiently high energies, or small

distances, at which the internal structure of composite objects

becomes apparent, we can safely live without knowing exactly how the

composite objects are constructed.

As usual, having defined elementary fields of particles that we want

to describe, we also have to postulate the corresponding Lagrangian

density. And as usual, we do that by writing a local function of fields

that is invariant with respect to all conserved symmetries. When we

have the nucleon and pion fields at our disposal, and we want to construct

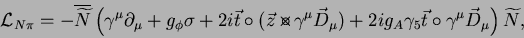

the Lorentz and chiral invariant Lagrangian density, the answer is:

![\begin{displaymath}

{\cal L}_{N\pi}

= - \bar{N}\left(\gamma^\mu\partial_\mu

+ ...

...left[\phi_4+2i\gamma_5\vec{t}\circ \vec{\phi}\right]\right)N .

\end{displaymath}](img165.png) |

(41) |

If you are not tired of this game of guessing the right Lagrangian

densities, you may wonder why the meson fields (within the

square brackets) appear in this particular form. To really see this, we have

to recall more detailed properties of the chiral group

SU(2) SU(2). Its generators

SU(2). Its generators  and

and  in the

spinor representation are given by Eq. (28), however, when

more than one quark is present, we have to use the analogous

generators

in the

spinor representation are given by Eq. (28), however, when

more than one quark is present, we have to use the analogous

generators  and

and  that are sums of

that are sums of  's and

's and

's for all quarks. In particular, the meson fields

's for all quarks. In particular, the meson fields  belong to the vector representation of SU(2)

belong to the vector representation of SU(2) SU(2). Then,

according to identification (35) and (37), the

first three components

SU(2). Then,

according to identification (35) and (37), the

first three components  form the isovector pion field,

and the fourth component

form the isovector pion field,

and the fourth component  is an isoscalar. This fixes the

transformation properties of

is an isoscalar. This fixes the

transformation properties of  with respect to the

iso-rotations, given by infinitesimal transformation

with respect to the

iso-rotations, given by infinitesimal transformation

. Since these rotations have identical

form as the real rotations in our three-dimensional space, we do not

show them explicitly. On the other hand, the transformation

properties of

. Since these rotations have identical

form as the real rotations in our three-dimensional space, we do not

show them explicitly. On the other hand, the transformation

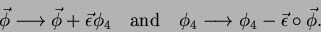

properties of  with respect to the chiral rotations, given by

infinitesimal transformation

with respect to the chiral rotations, given by

infinitesimal transformation

, are

, are

|

(42) |

There is no magic in this expression - one only has to properly

identify generators of the O(4) group with generators  and

and

. This is unique, once we fix which components (1,2,3 in our

case) transform under the action of

. This is unique, once we fix which components (1,2,3 in our

case) transform under the action of  . Under the chiral

rotation about the same angle

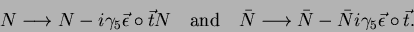

. Under the chiral

rotation about the same angle

, the nucleon fields

transform by infinitesimal transformation

, the nucleon fields

transform by infinitesimal transformation

,

within the spinor representation of Eq. (28), i.e.,

,

within the spinor representation of Eq. (28), i.e.,

|

(43) |

It is now a matter of a simple algebra to verify that Lagrangian

density (41) remains invariant under chiral rotations of

fields (42) and (43). Note that the first term in

Eq. (41) is separately chiral invariant, so we could

multiply the second term by an arbitrary constant  .

.

We can now proceed with the transformation to

better variables  and

and  , given by Eq. (35),

which gives,

, given by Eq. (35),

which gives,

|

(44) |

where

denotes vector product in the iso-space.

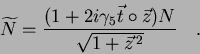

Covariant derivatives of pion fields

denotes vector product in the iso-space.

Covariant derivatives of pion fields  are defined

as in Eq. (39), and the chiral-rotated nucleon field

are defined

as in Eq. (39), and the chiral-rotated nucleon field

is defined as

is defined as

|

(45) |

There are several fantastic results obtained here. First of all,

the nucleon mass term

appears out of nowhere, and the nucleon mass,

appears out of nowhere, and the nucleon mass,

|

(46) |

is given by the chiral-symmetry-breaking value  of the

of the

field. In principle, we could begin by including the nucleon

mass term already in the initial Lagrangian density (41).

This is not necessary - the nucleon mass results from the same

chiral-symmetry-breaking mechanism that pushes scalar mesons up to

high energies. Second, the third term in Eq. (44) gives

the coupling of nucleons to mesons, and in the potential

approximation it yields the long-distance, low-energy tail of the

nucleon-nucleon interaction, i.e., the one-pion-exchange (OPE) Yukawa

potential Yuk35. Derivation of this potential from

Lagrangian density (44) requires some fluency in the

methods of quantum field theory, so we do not reproduce it here.

Suffice to say, that the OPE potential appears as naturally from

exchanging pions, as the Coulomb potential appears from exchanging

photons via the electron-photon coupling term in Eq. (16).

Last but not least, the last term in Eq. (44) gives the

axial-vector current that defines the weak coupling of nucleons to

electrons and neutrinos. From where phenomena like the

field. In principle, we could begin by including the nucleon

mass term already in the initial Lagrangian density (41).

This is not necessary - the nucleon mass results from the same

chiral-symmetry-breaking mechanism that pushes scalar mesons up to

high energies. Second, the third term in Eq. (44) gives

the coupling of nucleons to mesons, and in the potential

approximation it yields the long-distance, low-energy tail of the

nucleon-nucleon interaction, i.e., the one-pion-exchange (OPE) Yukawa

potential Yuk35. Derivation of this potential from

Lagrangian density (44) requires some fluency in the

methods of quantum field theory, so we do not reproduce it here.

Suffice to say, that the OPE potential appears as naturally from

exchanging pions, as the Coulomb potential appears from exchanging

photons via the electron-photon coupling term in Eq. (16).

Last but not least, the last term in Eq. (44) gives the

axial-vector current that defines the weak coupling of nucleons to

electrons and neutrinos. From where phenomena like the  decay

can be derived. [This term is an independent chiral invariant, so

again we could put a separate coupling constant there; experiment

gives

decay

can be derived. [This term is an independent chiral invariant, so

again we could put a separate coupling constant there; experiment

gives  =1.257(3).]

=1.257(3).]

Next: FEW-NUCLEON SYSTEMS

Up: Dynamical (Chiral) Symmetry Breaking

Previous: Pion-Pion Lagrangian

Jacek Dobaczewski

2003-01-27

![]() and

and ![]() , given by Eq. (35),

which gives,

, given by Eq. (35),

which gives,

appears out of nowhere, and the nucleon mass,

appears out of nowhere, and the nucleon mass,